The 90-hour portfolio week

Summary

While some sections of India Inc. ask for 70, 90 and 140-hour work weeks, the average worker has little or no leisure time. We’re all working close to 90-hour weeks already.

(This is part two in a two-part series about the 90-hour workweek. Read part one here.)

In my previous article, I addressed overwork advocacy by some members of India Inc., who’d like us to work for 70, 90 or even 140 hours each week. If you’ve read that article, you’ll know we can’t take the 40-hour workweek lightly. It’s a hard-fought win from over a century of labour struggle and deserves hard-fought protection. Indeed, most labour laws mandate overtime pay for overwork, and overtime can’t be unlimited.

I also addressed how incentives for overwork are unequal between the capitalists and the commoners. The top dogs usually earn disproportionately more from our overwork than we do. And given the high stakes of their jobs and colossal pay packages, it’s perhaps only fair that they work as much as they claim they do. For the rest of us, 8/8/8 is a fair formula.

Most blue-collar, unionised workforces demand overtime pay when the bosses ask for overtime. In contrast, white-collar workers, especially tech workers, often give away their time for free. One of the reasons for offering this free labour is the advent of “workism” - a term Derek Thompson coined six years ago.

“Workism is the belief that work is not only necessary to economic production but also the centrepiece of one’s identity and life’s purpose; and the belief that any policy to promote human welfare must always encourage more work.”

“A workist seeks meaning from their work similar to how a religious person seeks meaning from their faith.”

Work is worship. Just as a religious person doesn’t think twice about the time they spend on prayers or a visit to their place of worship, many white-collar workists don’t pay heed to the number of hours they spend working or their time in an office. If you take the religion metaphor a bit further, the bosses at work are what the pastors are at church. So, when the bosses preach or practice overwork, the workists often follow.

Of course, the bosses earn far more from a system of overwork than the average employee who endures a gruelling schedule in the name of culture, camaraderie, teamwork or extraordinary impact. The difference in rewards is stark in IT services, where employers bill their people’s time by the hour but often don’t voluntarily pay overtime. The extra hours improve the company’s revenue, fatten the bottom line, and give the executives a happy bank run. The most any employee may receive is an “Extra-miler award” at an all-hands meeting.

The trouble, however, is that we’re at a loss for what we’ll do if we don’t work. For instance, I once worked for a manager who checked their phone for emails and messages the moment they woke up. They’d send me tasks at odd hours over IM. When they couldn’t sleep, they’d scroll through IM and email to see where they could be involved. They even cut short their parenting leave because they got bored and couldn’t stay away from work. As SN Subhramanyan said,

“How long can you stare at your wife? How long can the wife stare at her husband? Get to the office and start working.”

Well, that’s the question I’d like to address in this post.

Leisure, what leisure?

When you read SN Subhramanyan’s quote, it feels like, outside employment, we spend all our waking hours in leisure activities. Such as staring at your spouse’s face. Nothing can be further from the truth.

People, who don't work 90 hours a week, in remaining hours pic.twitter.com/cwHBHskEOm

— Darshan Pathak (@darshanpathak) January 9, 2025

Leisure as a break from work has a fascinating history. In 1930, John Maynard Keynes wrote an essay titled “Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren”. It’s an engrossing read, and I urge you to check it out. But here’s a summary.

Keynes predicted a massive shift in the standard of living in developed countries, which has largely come true.

“I would predict that the standard of life in progressive countries one hundred years hence will be between four and eight times as high as it is today.”

Keynes was bullish about the prospect of leisure. Here’s what he said about the promise of economic and technological advancement.

“For the first time since his creation, man will be faced with his real, his permanent problem – how to use his freedom from pressing economic cares, how to occupy the leisure, which science and compound interest will have won for him…”

Keynes admitted that “everybody will need to do some work if he is to be contented,” but he predicted that “three-hour shifts or a fifteen-hour week” should be enough. Would you believe that in 1965, a U.S. Senate subcommittee report also predicted that by the year 2000, Americans would only work 20-hour weeks and enjoy seven weeks of annual vacation?

Keynes was wrong.

The Senate subcommittee was wrong.

Americans are working more than ever before.

And India Inc. wants Indians to work more than we did during the British Raj.

If leisure is “free time” that we use for “enjoyment” or when we’re unoccupied, then I argue that such opportunities are relatively scarce for most of us. Even for someone like me, who maintains strict work-life separation, there’s hardly ever a time to go to the cinema, eat out, take an introspective walk, or catch a concert or comedy show. And yes, to stare at my spouse’s face - a face that can launch a thousand ships!

I’d wager that most working parents struggle to find three to four hours of authentic leisure time during a typical week. If I’m wrong, correct me in the comments.

Boredom, its necessity and its scarcity

Doing nothing is not as bad as we think. In 2013, Sandi Mann and Rebekah Cadman published a study concluding that bored people performed better in subsequent creative tasks than the control group. A year later, Harvard Business Review published “The Creative Benefits of Boredom”, where David Burkus argued how boredom triggers mind-wandering, leading to novel ideas. Search “boredom and creativity” on any search engine; you’ll know where I’m getting at.

We need leisure to be genuinely bored so our minds can wander. We need to be able to walk without our phones, without the stress of work or chores, the upcoming release, or the impending next meeting. For most of us, however, such boredom is a scarce luxury.

90-hour “portfolio weeks”

Boredom is scarce because our weeks are always full. To be fair, most of us are already working approximately 90-hour weeks — more precisely, 90-hour portfolio weeks.

Each of us has a different portfolio of “work”. Here’s mine.

| Nature of work | Examples | Hours in a typical week | % of time |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep | Self explanatory. Human beings need 8 hours of sleep each day. | 56 | 33% |

| Health, hygiene and maintenance | Bathing, brushing, flossing, eating, exercising, etc. | 18 | 11% |

| Employment-related, paid work | Our day jobs. | 40 | 24% |

| Employment-related, unpaid work | Learning new skills for our employers or careers, commuting to work, etc. | 20 | 12% |

| Moonlighting projects | Projects that don’t conflict or coalesce with work. For example, I spend time on www.sumeetmoghe.com and www.asyncagile.org. | 7 | 4% |

| Parenting | Self explanatory. | 6 | 4% |

| Housework | Cooking, cleaning, home maintenance, errands, etc. | 12 | 7% |

| Intellectual stimulation | Reading, consuming news, listening to podcasts, etc. | 7 | 4% |

| True leisure | Free time to enjoy yourself as you please or do nothing if you’d like. | 2 | 1% |

This is what my portfolio week looks like

As you can see, the average week for me has very little time left for true leisure, a.k.a “free time” where I can stare at my wife’s face if she’s also free at the same time. Heck, I spend more time on employment-related, unpaid work than I spend on parenting. If you total my hours across employment-related work, moonlighting and domestic responsibilities, I’m already clocking 85 hours in a typical week.

Now, I admit that some people may not be parents. Others may not care enough about intellectual stimulation, moonlighting or personal development. Their portfolio may look different.

Elites like SN Subhramanyan probably have drivers, butlers, babysitters, housemaids, and other staff to do housework and parenting. They get paid enough that there’s no need or scope for moonlighting or unpaid work. Their portfolios will undoubtedly look different.

One way or another, I’m confident that most middle-aged workers, especially parents, have little time for leisure; however they organise their portfolios. And the look of those portfolios is down to what they value in life.

Extraordinariness is overrated

Looking at my portfolio, you may already understand my values, though I wish I could live differently. It’s fair to assume a few things about me.

I do my fair share of housework.

I value intellectual stimulation and learning.

I value projects outside work to keep myself sharp and fresh.

I spend very little time on parenting, though I should do more.

Am I achieving anything extraordinary through such a life? Maybe. Maybe not. Let’s pause before we answer that question. To make my point, I want to present a photograph from my childhood - Valentine’s Day 1990.

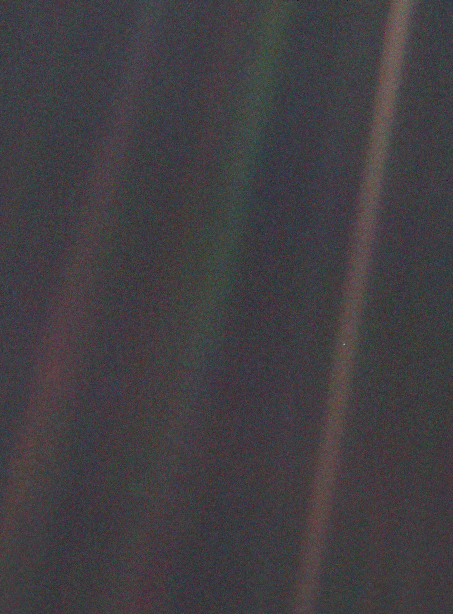

Pale Blue Dot - A photograph of Earth taken by the Voyager 1 spacecraft

Look hard, and you’ll see a pale blue dot. The Voyager 1 spacecraft took that photo from about 6.4 billion kilometres away. In the scattered light rays, our planet looks insignificant.

This photo inspired Carl Sagan's timeless essay “The Pale Blue Dot.” You can read it here or find the graphic version on ZenPencils. It’s one of the most humbling texts I’ve read, and a few lines are unforgettable.

Sagan described Earth’s appearance in this photo as “a mote of dust suspended on a sunbeam”. Every human we’ve ever known has inhabited and died on this pale blue dot. Ashes to ashes. Dust to dust. Sagan reminded us of our insignificance through these lines.

“Our posturings, our imagined self-importance, the delusion that we have some privileged position in the universe, are challenged by this point of pale light.”

Regardless of how important you think you are or the “extraordinary impact” you believe you’ll make, your extra lines of code, your fancy spreadsheet, your Zoom calls or your split-second responses on Slack mean very little in the larger scheme of things.

When explaining his idea of “cosmic insignificance”, Oliver Burkemann quotes the philosopher Iddo Landau.

“It is implausible, for almost all people, to demand of themselves that they be a Michelangelo, a Mozart, or an Einstein. There have only been a few dozen such people in the entire history of humanity. In other words, you almost certainly won’t put a dent in the universe. Indeed, depending on the stringency of your criteria, even Steve Jobs, who coined that phrase, failed to leave such a dent. Perhaps the iPhone will be remembered for more generations than anything you or I will ever accomplish but from a truly cosmic view, it will soon be forgotten, like everything else.”

To have a remarkable or extraordinary life is as easy as it is impossible. There was only one Oppenheimer, one Michael Phelps, one Sachin Tendulkar, and one Mandela. They’re once-in-a-generation geniuses for a reason. You and I are unlikely to be one of them, regardless of what our mums think about our “unrealised potential”.

Most companies have only so much room in the C-suite or the next management tier. Even if you manage to get to that tier, you’ll unlikely be remarkable enough for anyone outside your industry to know your name. I didn’t know about SN Subhramanyan until his latest shenanigans.

Most of us will fall short when we hold ourselves to these arbitrary, often unattainable notions of extraordinariness. Why should a tech company's founder or head honcho tell us how to make our life remarkable? Burkemann recommends that we recalibrate our yardsticks with what matters to us. Our lives will always be insignificant when a spacecraft photographs the planet from a few billion kilometres away. We might as well be happy and contented while being this insignificant.

I know I’m lucky to be married to the most attractive woman I know. I’ve never got tired of looking into her big, beautiful eyes. I must thank Mr Subhramanyan for reminding me to stare at her more often.

You’d agree I should spend more time looking into my wife’s face, right?

As for work hours, I’m sure you’ll realise you’re working quite a bit already if you consider your portfolio week. If anything, our employers will do well to free up time for us to enjoy boredom and leisure. How awesome would that be? We can wish, can’t we?