Adopt asynchronous collaboration in your distributed team

Summary

A meeting-centric way of working on distributed teams can undermine deep work and flow, inclusion, flexible work and in the long run knowledge sharing. It also doesn’t lend itself to scale. Choosing asynchronous ways to collaborate can be an effective alternative to this meeting-centric approach.

Being “async-first” is not about being “async-only”. It’s about recognising the benefits of asynchronous and synchronous communication patterns and being thoughtful about when you use either. The default, of course, is to start most collaborations, asynchronously.

To adopt an async-first approach, you must find workable asynchronous collaboration alternatives such as replacing status update meetings with up-to-date task boards, or by replacing onboarding presentations with self-paced videos.

Conduct a baselining exercise to assess your team’s current maturity with distributed work practices. The exercise will help you identify outcomes that asynchronous collaboration can help improve.

To accelerate your async-first shift, document your workflow, simplify your decision-making process, create a team handbook, and conduct a meeting audit.

A version of this article first appeared on InfoQ.

Do you work on a distributed team? If so, you know that meetings can be a major time-sink. While meetings can be valuable, if we reach for them as a default way of working, we inadvertently create a fragmented team calendar. Such an interrupted schedule can be a major drain on productivity, especially for knowledge workers who need time to focus on deep work. In this article, we'll discuss the benefits of asynchronous collaboration and how to implement it on your team.

Just. Too many. Meetings.

“We have too many meetings!” As a leader or a member of a distributed team, you probably hear this complaint all the time. It won’t be surprising if you heard it last when you were in a meeting. While the pandemic drove up the number of meetings we find ourselves in, many teams have always had a meeting-centric collaboration approach. Between design discussions, status updates, reporting calls, daily standups, planning meetings, development kick-offs, desk checks, demos, reviews and retrospectives, an average software development iteration packs in several such “synchronous” commitments. And those aren’t the only meetings we have! Ad hoc conversations, troubleshooting sessions, brainstorms, problem-solving, and decision-making - they all become meetings on distributed teams.

Between 2021 and 2022, I conducted an informal survey targeting over 1800 technologists in India. I wanted to understand their distributed work patterns. Amongst other questions, the survey asked respondents to estimate how many hours of meetings they attended each week. It also asked people to estimate how many times they checked instant messages each day. The responses were astonishing.

The average technologist spent 14 hours in meetings each week, which amounts to 80 days each year in meetings. As you may guess, the most experienced technologists face even more of the meeting burden.

People reported facing 18 interruptions on average, each day. The culprit? Instant messaging - a tool we employ for “quick responses”.

A slice of my survey results

Software development is inherently a creative process, whether you’re writing code, crafting an interaction or designing a screen. Leadership on software teams is a creative exercise too. Many of us spend time building technical roadmaps, articulating architectural decisions, prototyping, designing algorithms and analysing code. As Paul Graham noted in his 2009 essay, software development is a “maker’s” job (i.e. a job that’s creative) , which needs a “maker’s schedule”. “You can't write or program well in units of an hour. That's barely enough time to get started.”, Graham said back in the day. On a maker’s schedule, where people need “units of half a day at least”, meetings and interruptions are productivity kryptonite.

Unsurprisingly, this sentiment showed up in my surveys as well. The average technologist desires about 20 hours of deep work each week, but they get just 11. Imagine how much more every team can achieve if we could somehow buy back those lost hours of deep work.

Enter, “async-first” collaboration. It’s a simple concept that prioritises asynchronous collaboration over synchronous collaboration. I describe it through three underlying principles.

Meetings are the last resort, not the first option.

Writing is the primary means of communicating information in a distributed team.

Everyone on the team builds comfort with reasonable lags in communication.

I understand if you’re dismayed by the first principle. In many organisational settings, meetings are indeed the primary tool for leaders to do their work. We can, however, agree on two fundamental observations.

For most of your team, a trigger-happy approach to meetings can lead to an interrupted, unsatisfying, and even unproductive day. As leaders, we owe it to our team to create a work environment where they can experience a state of flow.

Many meetings are unproductive because of a lack of prep, a lack of subsequent documentation and a poorly identified audience. When we go “async-first”, we force ourselves to prepare well for a synchronous interaction if we need one. It helps us think about who we need for the meeting and how we’ll communicate the outputs of the meeting to people who don’t attend it

So, instead of reaching for a meeting the next time you wish to collaborate with your colleagues, consider if a slower, asynchronous medium may be more effective. You can use collaborative documents that support inline discussion, wikis, recorded video and even messaging and email.

Allow me to explain why you and your team will benefit from this async-first mindset and how you can adopt it, in your context.

The six benefits of going async-first

Ever since the pandemic-induced remote work revolution, knowledge workers now expect employers to offer location and time flexibility. Return-to-office drives from various employers notwithstanding, it’s fair to assume that some of our colleagues will always be remote in relation to us. This apart, even in a recession, companies are struggling to fill open tech positions. When markets pick up as they inevitably will, at some point, tech talent will feel even more scarce. Companies will have to hire people from wherever they can find them, and they’ll have to integrate them into their teams. Tech teams will be “distributed by default”. This is where an “async-first” collaboration approach can outshine the meeting-centric status quo.

| Benefit | How asynchronous work helps |

|---|---|

| Work-life balance | When your team has people from across the country or even across the world, you don’t have to force-fit them into working a specific set of hours. People can choose the work hours that work best for them. Their life doesn’t have to compromise with their work. |

| Diversity and inclusion | In synchronous interactions; i.e. meetings; we often don’t hear from introverts, non-native English speakers and neurodiverse people. Often the loudest, most fluent and most experienced voices win out. In an async-first environment, the people who aren’t confident speaking can use the safety of tools and writing, to communicate freely. Since async-first collaboration can help people work during the hours convenient to them, it helps people with various personal situations, to become part of your team. |

| Improved onboarding and knowledge sharing | Writing is the primary mode of communication on an async-first team. Regular writing and curation help build up referenceable team knowledge that you can use for knowledge sharing and onboarding. It also reduces FOMO. |

| Communication practices that support scale |

Everyone can’t be in every meeting. That’s the perfect way to burn out your colleagues. People can read faster than they listen. They don’t remember every piece of information they encounter. This makes referenceability critical, especially on distributed teams. Writing allows your team to share information at scale. It’s referenceable, fast to consume and easy to modify and update. |

| Deep work | When you don’t have unnecessary meetings on your calendar, you can now free up large chunks of time to get deep, complex work done without interruptions. This has a direct impact on the quality of the work you do as a team. |

| A bias for action | When you work asynchronously, you’ll inevitably get stuck at some point. The usual choice in a meeting-centric culture would be to get a bunch of people on Zoom to make a decision. After all, you don’t want to screw up, do you? In an async-first culture though, we adopt a bias for action. We make the best decision we can at the moment, document it, and move on. The focus is on getting things done. If something’s wrong, we learn from it, refactor and adapt. The bias for action improves the team’s ability to make and record decisions. Decisions are, after all, the fuel for high-performing teams. |

All these benefits aside, an async-first culture also helps you improve your meetings. When you make meetings the last resort, the meetings you have, are the ones you need. You’ll gain back the time and focus to make these few, purposeful meetings useful to everyone who attends.

Async-first is not async-only

Going async-first does not mean that synchronous interactions are not valuable. Team interactions benefit from a fine balance between asynchronous and synchronous collaboration. On distributed teams, this balance should tilt towards the asynchronous, lest you fill everyone’s calendars with 80 days of meetings a year. That said, you can’t ignore the value of synchronous collaboration.

Written communication allows you to be slow, deliberate and thoughtful about your communication. You can write something up independently and share it with your colleagues without having to get on a call. It also allows you to achieve depth that you may not achieve in a fast-paced, real-time conversation. Everything you write is reusable and referenceable in the future as well. These are the reasons that asynchronous communication can be very effective. Let’s look at a few examples.

Imagine an architect documenting a proposal to use a new library by explaining the various dimensions of the proposal -e.g. integration plan, testing, validation, risks and alternatives. It can help bring the entire team and business stakeholders onboard in a short time.

When team members document the project in the flow of their work, through artefacts such as meeting minutes, architectural decision records, commit messages, pull requests, idea papers or design documents, it builds the collective memory of the project team. This helps you build the archaeology of your project, that helps explain how you got to your current state.

Each of the above examples can benefit from both team members and leaders collaborating. e.g. when a leader proposes to use the new library, team members can comment inline on the wiki page and share concerns, ideas, feedback and suggestions. In a similar way, a junior team member can create a pull request to trigger a code review, while a team lead must provide useful feedback when reviewing the pull request. This is how written communication becomes a collaborative exercise.

On the flip-side, synchronous communication helps you address urgent problems. This is where real-time messaging or video conferencing comes in handy. Every activity isn’t urgent though. Applying the pattern of synchronous work to non-urgent activities, often comes with the “price” of interruptions to flow. This is why we must balance synchrony and asynchrony!

Similarly, when you have to address a wide range of topics in a short time, or when you’re looking for spontaneous, unfiltered reactions and ideas you’ll want to go synchronous. And you’ll agree that after a while, most people want some “human” connection with their colleagues; especially on remote and distributed teams. This too, is where synchronous communication shines.

Asynchronous vs synchronous communication – the balance of values

So remember - “async-first” is not “async-only”. Think about the balance of collaboration patterns on your team as a set of tradeoffs. Use the right pattern for the right purpose.

How not to go async-first

The idea of async-first is deceptively simple. Meet less, write more, embrace lag - it’s an uncomplicated mantra. However, I’ve found that many teams struggle to adopt this approach. There are a few reasons for this.

Collaboration patterns work when everyone buys into them. That’s when the “network effect” kicks. If a few people work async-first and the rest work in a meeting-centric way, you’re unlikely to see the benefits you’re aiming for.

Teams already practise many synchronous rituals that recur on their calendars - e.g. standups, huddles, reporting calls and planning. It’s hard to replace these rituals with async processes while still retaining their value, without careful thought.

Any change in collaboration patterns leads to a period of confusion and chaos. During this time, the team will see a dip in productivity before they see any benefits. Teams that don’t plan for this dip in productivity may give up on the change well before they’ve realised the benefits.

So, to make any new ways of working stick, you need business buy-in and team buy-in first. After that, you must go practice-by-practice and ensure that you don’t lose any value when introducing the new way of doing things. The same goes for async-first collaboration.

What it takes for a successful change to ways of working

Prepare to go “async-first” with your team

Assuming that the business sees the problem with too many meetings and so does the team, you should have some buy-in from these stakeholders already. To prioritise your areas of focus, I suggest polling your team to learn which of the six benefits they prize more than the others.

Reflecting as a team on the current state of your collaboration practices is a great way to prepare to be async-first. I recommend asking four sets of questions.

How diligent are you with the artefacts you create in the flow of your work? E.g. decision records, commit messages, READMEs and pull requests. Such artefacts lay the foundation of working out loud, in an async-first culture.

How disciplined are you with the meetings you run? Think about things like pre-defined agendas, nominated facilitators, time boxes and minutes. Do people have the safety to decline meetings where they won’t add or derive value? Are meeting sizes usually small; i.e. 8 people or fewer? Effective meetings are a side-effect of an effective async-first way of working.

How much time do you already get for deep work? How much time would you want instead, each day? What’s the deficit between the time the team wants, versus what it already gets?

How easy is it to onboard someone to your team? How much time does it take for someone to make their first commit, after they’ve got access to your systems? Onboarding as a process is a test for how well-documented your ways of working are.

The above questions will help you establish a baseline for your team’s maturity with distributed work practices. It’ll also help you identify areas for improvement that you can target, with your async-first shift. I suggest using a survey tool to assess this baseline, because it’s simple, and it’s… well… asynchronous!

Publish the results of this survey to the team and highlight the gaps, so they’re clear to everyone. That way it’s always clear why you’re going async-first, and what benefits you hope to get.

The fundamental shifts

In my experience every team’s shift to async-first ways of working is different. Indeed, teams that go through the baselining exercise I’ve recommended, often pick different areas to improve through asynchronous collaboration. There are a few fundamental shifts that I recommend every team makes.

Define your workflow

We all value “self-organising teams” and “autonomy” at work. However, as Cal Newport says in his book, “A World Without Email”, knowledge work is a combination of “work execution”, and “workflow”. While every individual should have autonomy over their work execution, teams must explicitly define their workflow and not leave it to guesswork. For example, you’ll notice that the screenshot below describes my current team’s two-track development approach. It spells out everyone’s responsibilities and how work flows through our team’s system. We’ve also set our team’s task board to implement this workflow.

Defining your workflow avoids confusion in async-first teams (example)

When you document your development process this way, it reduces meetings that arise from the confusion of not knowing who does what, or what the next step is. It also becomes a ready reference for anyone new to the team. You don’t need a meeting to explain your development process to new colleagues. Write once and run many times!

Push decisions to the lowest level

Too often teams get into huddles and meetings for every single decision they make. Not only does this coordination have a cost, it also leads to several interruptions to work. It also leads to risk-averse teams. As a first step, work with your team to define the categories of decisions that are irreversible, in your project context. Don’t be surprised if there are very few such categories. Continuous delivery practices have matured to a point that almost all decisions in software are reversible, except the ones that have financial, compliance or regulatory impacts. Only these decisions need consensus-style decision-making. Other, reversible decisions can take a more lightweight approach.

For example, each time someone wants to decide something and wishes to seek other people’s inputs, they can write up the decision record and invite comments on it. If the decision is reversible, and there are no show-stopping concerns, they go ahead, while acting on workable suggestions. You can even organise large teams into small, short-lived pods of two or three people, along feature or capability lines, as you see in the diagram below. Each pod can have a directly responsible individual (DRI), who is accountable for decisions the pod makes. The DRI shouldn’t be an overhead. They should instead be a “first-amongst-equals” (FaE). Organising this way has three distinct features.

Individuals can still adopt asynchronous decision-making techniques, but when there’s a difference of opinions, the DRI can play the tie-breaker

You reduce the blast radius of communication, especially when you need a meeting. The pod owns its decisions for the capability it’s building. They decide and then share the record in a place where it’s visible to all other pods.

You can still rotate people across pods to facilitate expertise sharing and resilience. That way you improve decision making autonomy while still helping team members build familiarity with the entire codebase.

Organising large teams into pods, to reduce the blast radius of decisions

Create a team handbook

High-quality documentation is a catalyst for asynchronous collaboration. Every software team should have one place to store team knowledge and documents - from decisions to reports to explainers to design documents and proposals. I call this the “team handbook”. There are ubiquitous tools that your team already uses, that you can employ for this purpose - Confluence, GitLab, SharePoint, Notion, Almanac, Mediawiki - are some that come to mind.

Spend some time planning the initial structure of your handbook with your team and organise lightweight barn-raising activities to set up the first version. From that point on, the team should own the handbook just as they collectively own their codebase. Improve it and restructure it as your team’s needs change.

An example of a team handbook

Reduce the mass of meetings

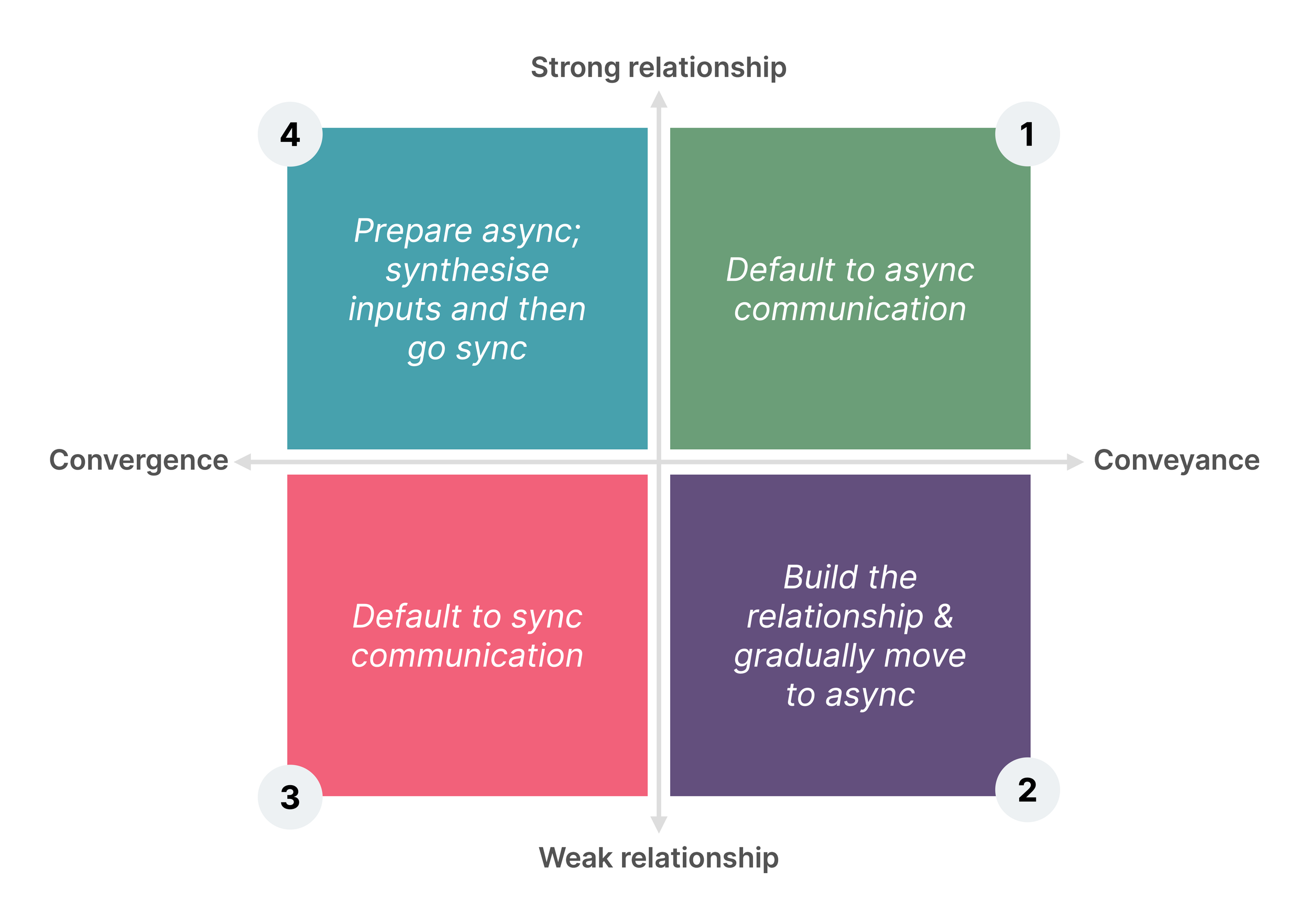

Teams that’ve been together for a while, often accumulate many rituals and commitments. On distributed teams, these commitments show up as meetings on the team calendar. It’s not uncommon for teams to be committed to 10 hours of meetings per sprint, simply through recurring meetings. To go async-first, it helps to trim down your team’s meeting list to the necessary ones. I use a framework that I call the ConveRel quadrants, to help teams identify which meetings they need and which meetings they can replace with asynchronous communication.

The framework is a standard 2x2 matrix. The x-axis represents the nature of communication. On the right side, you have “conveyance”. An example would be one-way information transfer. The left side of the axis stands for “convergence”. An example would be a workshop to make a high-stakes decision.

The y-axis denotes the strength of the relationship between the people communicating. The top half denotes a strong relationship and the bottom, a weak relationship.

You can plot your team’s meetings into the quadrants of this matrix to decide how they change when you go async-first.

If you’re only trying to convey information to people you have strong relationships with, don’t do meetings. Instead, make the information available online by sharing a document or wiki page or by sending an email or a message. This is as easy as it gets. Most status updates and reporting calls fit in this quadrant.

If the relationship is weak though, you may need some interactions to build up the relationship. Conveying information can be a contrivance for building that camaraderie. As the relationship gets stronger, replace these interactions with asynchronous ones.

If your relationship is weak and you’re trying to converge on a decision, I suggest defaulting to a meeting.

And finally, if your relationship is strong, and you’re trying to converge on a decision, you must collect all inputs asynchronously, do everything you can outside a meeting and then get together only for the last step.

The ConveRel quadrants

A simple meeting audit using the ConveRel quadrants can not only help you identify meetings you can replace with asynchronous processes, you’ll also be able to improve the meetings you keep.

With these fundamental shifts in place, you’ll have made some of the biggest improvements to help you work asynchronously. You can now work with your team to assess each practice that you execute over ad hoc video-calls and find asynchronous alternatives instead. This will take time, so address one or two improvements every development cycle and see how you go from there.

In summary

Async-first collaboration can help your distributed team become more efficient, inclusive, thoughtful, and fun to work in. It isn’t an overnight shift though. Many of us default to a synchronous way of working, because it mimics the office-culture which we were part of, before the pandemic. This, as we’ve learned, generates team calendars full of meetings!

If you wish to help your team be more asynchronous in their ways of working, you must enlist not just their support, but that of the business, so you have the space to absorb change. As part of this change process examine your team’s collaboration processes and be sure to find workable asynchronous alternatives. The idea is to not just reduce interruptions but also preserve the value that the team got from the synchronous variants.

Remember the value of reflection when directing this shift. A baselining exercise where you assess your team’s distributed work maturity, will help you mark the starting point. From that point, each change you influence should be in service of nudging your team towards the benefits it seeks. Start by working with your team to document your workflow, simplify your decision-making process, create a team handbook, and to conduct a meeting audit. That start will set the foundation for other, smaller, iterative improvements that you’ll make to each of your collaboration processes.